Effective communities are typically assumed to involve rich networks of trusting relationships that enable the community to sustain cooperation and achieve mutual goals. But such rich social ties are rarely, if ever, found in today’s urban communities. Nonetheless, sociologist Robert Sampson believes that trust is still vital in sustaining cooperative behavior in modern cities.

Effective communities are typically assumed to involve rich networks of trusting relationships that enable the community to sustain cooperation and achieve mutual goals. But such rich social ties are rarely, if ever, found in today’s urban communities. Nonetheless, sociologist Robert Sampson believes that trust is still vital in sustaining cooperative behavior in modern cities.

Along with facilitating the flow of labor, capital, and information across national boundaries, globalization is also sparking a resurgence of immigration--much of it directed to the United States. Most immigration research either focuses on a group's attachment to its home country or on its integration in the receiving society. Ewa Morawska has designed a unique project to explore the extent to which different groups of immigrants maintain connections with their homeland, assimilate to life in the United States, or hold ties to both countries.

According to the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the Dominican Republic was the sixth largest contributor of immigrants to the United States in the 1980s and the fifth largest in the 1990s. Dominicans bring with them a different understanding of racial classification than exists in American society. The main sociocultural trend in the Dominican Republic is intermediate racial categorization, allowing people to distance themselves from blackness. Upon migration to the United States, Dominicans confront a binary system of racial categorization that classifies them simply as black.

The success of immigrants can best be measured by the success of their children--and of their children's children--who are born or raised in the adopted homeland. Richard Alba, of SUNY Albany, has posited three outcomes facing immigrant groups: conventional assimilation into the mainstream; ethnic pluralism whereby a group takes advantage of its ethnicity (the subeconomy created by Cubans in Miami and various Chinatowns, for example) while remaining closely connected to its home country; or segmented assimilation into a disadvantaged minority group or cultural ghetto.

Despite the fact that people of Mexican origin are the largest immigrant group in the United States, little is known about the long-term course of their adaptation and assimilation into U.S. society. Are they progressing on a long path towards middle class status or are they engaging in behavior that will leave them idling at the low end of the economic distribution?

The U.S. Department of State and the Immigration and Naturalization Service conduct an annual "Diversity Lottery" that allows adults who were born in under-represented source countries a chance to gain legal, permanent residency in the United States. In recent years, 8 to 12 million people from over 150 countries applied for a chance to obtain one of 50,000 green cards through a random selection. Despite the lottery's impact on these millions of people and the immigrant population in the United States, little is known about the role the program plays in contemporary U.S.

Immigrants from the Dominican Republic have faced a difficult transition to life in the United States. They and their children suffer from high poverty rates as well as poor educational and occupational outcomes. They are currently undergoing a large geographic shift - moving out of the areas in which they initially settled and into new communities, which are often smaller and have weaker economies.

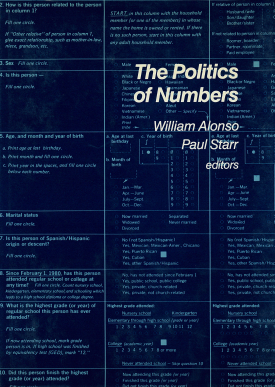

The Politics of Numbers

About This Book

The Politics of Numbers is the first major study of the social and political forces behind the nation's statistics. In more than a dozen essays, its editors and authors look at the controversies and choices embodied in key decisions about how we count—in measuring the state of the economy, for example, or enumerating ethnic groups. They also examine the implications of an expanding system of official data collection, of new computer technology, and of the shift of information resources intot he private sector.

WILLIAM ALONSO is at Harvard University.

PAUL STARR is at Princeton University.

A Volume in the RSF Census Series

RSF Journal

View Book Series

Sign Up For Our Mailing List

Apply For Funding

For most of the last century, the promise of upward mobility proved true for highly motivated and hard-working immigrants to the United States. Each succeeding generation of these white ethnic groups achieved more education and better jobs than the one before, notwithstanding initial social and economic discrimination, and harsh living conditions. At the beginning of a new century, however, the assumptions of upward mobility for new immigrants and their children have become more uncertain.

Pagination

- Previous page

- Page 86

- Next page