Main navigation

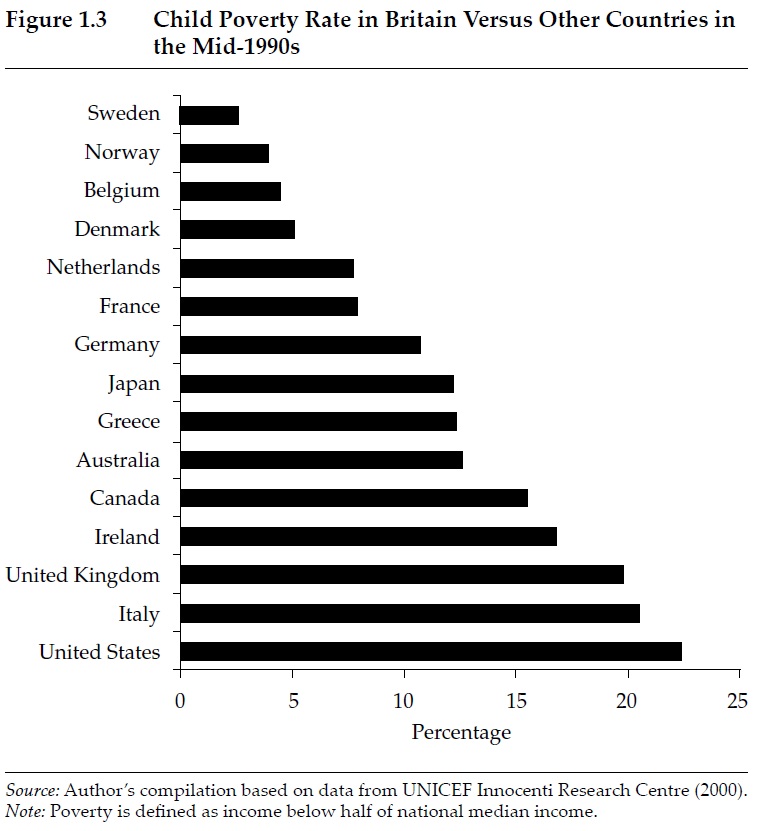

In March 1999, U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair made a remarkable pledge before a startled audience: "Our historic aim will be for ours to be the first generation to end child poverty," he said. "It will take a generation. It is a 20-year mission. But I believe that it can be done if we reform the welfare state and build it around the needs of families and children." The unexpected announcement came in the midst of an alarming rise in the country's child poverty, which hovered around the 20 percent level by the mid-1990s. (See Figure 1.3 below for an international comparison; poverty was defined as income below half of the country's median income). But would such an ambitious pledge make a difference? With its echoes of Lyndon Johnson's "war on poverty" speech, now often cited in conservative circles as evidence of policy hubris, would Blair's ambition merely reveal the intractable problems underlying poverty?

In March 1999, U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair made a remarkable pledge before a startled audience: "Our historic aim will be for ours to be the first generation to end child poverty," he said. "It will take a generation. It is a 20-year mission. But I believe that it can be done if we reform the welfare state and build it around the needs of families and children." The unexpected announcement came in the midst of an alarming rise in the country's child poverty, which hovered around the 20 percent level by the mid-1990s. (See Figure 1.3 below for an international comparison; poverty was defined as income below half of the country's median income). But would such an ambitious pledge make a difference? With its echoes of Lyndon Johnson's "war on poverty" speech, now often cited in conservative circles as evidence of policy hubris, would Blair's ambition merely reveal the intractable problems underlying poverty?

In her RSF book Britain's War on Poverty, researcher Jane Waldfogel evaluates the three-pronged anti-poverty strategy the British government enacted and, one decade after Blair's speech, finds a substantial reduction in child poverty. The extent of the decline depends on which measure you use—the British prefer a relative poverty measure, under which a child is poor if his or her family has income below 60 percent of median income for a family of their size in that year. This is, Waldfogel notes, a difficult measure to make progress on because if median incomes rise, relative poverty also rises unless those on the bottom make more money as well. Here in the United States, the government uses an absolute poverty measure, under which a child is poor if his or her family's income is below a fixed number (the poverty line in 2010 for a family of four was $22,314).

So how did Great Britain do? In 1999, 3.4 million children—one in four—were in poverty, whether defined in relative or absolute terms. By 2007-2008, using the absolute measure, the number of poor children had fallen to 1.7 million, a 50 percent decrease. Progress was less remarkable using the relative measure, but the child poverty rate fell from 26.7 percent in 1998-1999 to 22.5 percent in 2007-2008. The decrease seems small, but one should remember that during this period, median incomes in Britain rose roughly 50 percent—that means more low-income children were counted as poor even if their incomes had not fallen in real terms. Consider also the progress—of lack of it—made in the United States during this same period. (See Figure 6.1 below.)

MAKING WORK PAY

In her book, and at her 2012 Doris lecture at Cornell University (see below), Waldfogel describes the three-pronged approach Britain took to fight child poverty and compares its policies with the ones enacted in the United States after welfare reform in 1996. We offer a brief overview of these initiatives here. First, policymakers hoped to encourage more low-income parents to work, and to make work pay. The government introduced the first national minimum wage in Britain, setting its initial value at 45 percent of median British hourly earnings, compared to the 38 percent level in the United States. The minimum wage grew more generous over time; by 2009, it was set at a value of about 50 percent of median British hourly earnings, as opposed to about 40 percent in the U.S. The Labor government also enacted a tax credit modeled on the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) aimed at parents who worked more than sixteen hours per week. Crucially, the tax credit could be claimed throughout the year; in the U.S., workers only receive the EITC when they file their annual tax returns.

SUPPORTING FAMILIES WITH CHILDREN

While the above legislation relied on evidence from American policy experiments, British lawmakers broke from the American tradition in a fundamental way: they decided to also increase financial support for all families with children, whether or not the parents worked. "Over the period of welfare reform, [the United States] increasingly made support for children contingent on parental employment," Waldfogel writes. Instead, the U.K. significantly increase the value of the universal child allowance and introduced a child tax credit that went to all but the richest families. Taken together, these investments substantially raised the amount of support families with children receive: by 2006, the average family with children had gained £1,500 per year in real terms, while the bottom 20 percent had gained £3,400.

INVESTING IN CHILDREN

The final component of Britain's anti-poverty strategy increased investments and services for children. Universal preschool for all four-year-olds was introduced and gradually moved Britain from having one of the lowest preschool enrollment rates in Europe to being on a par with its European peers. Paid maternity leave was extended to nine months and paid paternity leave for two weeks was also enacted (an option both Blair and his successor David Cameron used while in office). Other initiatives sought to reduce class size and require schools to offer a literacy and math hour, which required teachers to spend an hour each on reading and math instruction.

ADDING THE COSTS

Taken together, these antipoverty initiatives amounted to nearly £9 billion per year, or roughly 1 percent of Britain's gross domestic product. (The equivalent value in America would amount to $130 billion.) Given the promising results, Waldfogel argues that the U.S. could learn much from Britain's efforts. "This is pretty easy to do," she says in her lecture. "If we think there's nothing government can do to reduce child poverty, if we think this is intractable, I hope I have persuaded you that this example clearly provides evidence to the contrary. It's really just a matter of political will."

Buy a copy of Britain's War on Poverty, or read the introduction to her book for free.