Here are links to some of the interesting social science research we encountered during the week:

Between 2007 and 2010, sociologists Jeff Manza and Clem Brooks conducted three nationally representative surveys to systematically examine Americans' attitudes toward counterterrorism policies. Their data, published in our new book, Whose Rights? Counterterrorism and the Dark Side of American Public Opinion, offer an interesting empirical perspective on American attitudes at a time when the debate over the use of drones, extrajudicial killings and extraordinary rendition has re-emerged. Here is an excerpt from the volume:

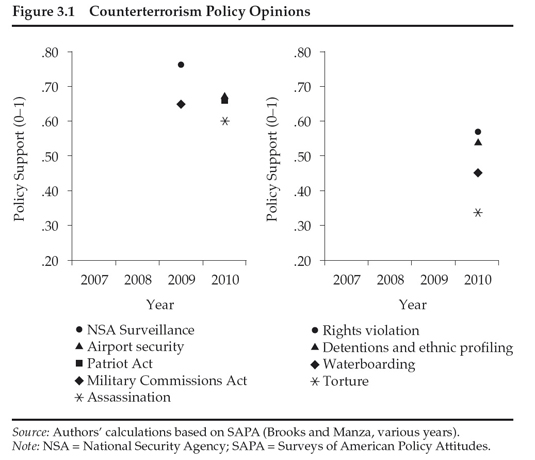

Figure 3.1 presents our analysis of these data, and symbols indicate the mean level of support for a specific counterterrorism policy or practice. [The survey's] counterterrorism items have a range of 0 through 1, higher scores indicating greater support. Of the ten policies and practices at hand, it is NSA surveillance of American citizens and suspected terrorists that elicits the highest level of support. With a score of 0.76, the NSA surveillance item’s score is well above levels of support for the next three counterterrorism items, all of which cluster together: airport security (0.67), the Patriot Act (0.66), and the Military Commissions Act (0.65). Next is assassination, where the targeting of “individuals suspected of being al-Qaeda or Taliban leaders” receives a score of 0.60.

These first five counterterrorism items show what amounts to a fair amount of support. All scores are well above the 0.50 scale midpoint. The right panel of figure 3.1 presents data for the remaining five items. The rights violation item leads the way, 0.57 indicating that respondents’ average opinion is shaded toward agreement with the position of taking “all steps necessary to prevent additional acts of terrorism.” Not far behind are opinions on detention, the mean for which is 0.54. In the 2010 SAPA survey, the detention and ethnic profiling items have the same item score of 0.54. The waterboarding item is next with a score of 0.45. With an even lower score of 0.34, the practice of torture easily elicits the highest level of public opposition. Given that waterboarding is best understood as a subset of torture, the contrast between opinions on these two counterterrorism practices merits a note in passing because it anticipates the cognitively induced framing effects we probe more systematically in chapters 4 through 6.

RSF grantee Roger Waldinger has co-authored a new paper, "Inheriting the Homeland? Intergenerational Transmission of Cross-Border Ties in Migrant Families," in the latest issue of the American Journal of Sociology. Here is the abstract:

Theories of migrant transnationalism emphasize the enduring imprint of the premigration connections that the newcomers bring with them. But how do the children of migrants raised in the parents’ adopted country develop ties to the parental home country? Using a structural equation model and data from a recent survey of adult immigrant offspring in Los Angeles, this article shows that second-generation cross-border activities are strongly affected by earlier experiences of and exposure to home country influences. Socialization in the parental household is powerful, transmitting distinct home country competencies, loyalties, and ties, but not a coherent package of transnationalism. Our analysis of five measures of cross-border activities and loyalties among the grown children of migrants shows that transmission is specific to the social logic underlying the connection: activities rooted in family relationships such as remitting are transmitted differently than emotional attachments to the parents’ home country.

Here are links to some of the interesting social science research we encountered during the week:

Late last year, the Russell Sage and Alfred P. Sloan Foundations sponsored a competition to solicit proposals for smart disclosure demonstration projects. "Smart disclosure" policies aim to improve consumer markets by providing decision-makers data about their their personal use patterns or histories. Here are some details on the winning proposals:

1. Efficient Web-Based Credit Markets

While the consumer credit market has grown dramatically in the past two decades, consumers find it difficult to systematically compare credit offers (many of which arrive in the mail). Consumers know that their credit score may be downgraded by repeated applications for credit, but a bigger challenge is sorting through lengthy contracts, complicated reward programs, and interest rates. This research project will investigate the potential of a recent policy shift in Sweden, where consumers can "shop" for credit using an online intermediary. When they submit their information -- for example, the amount of credit they seek and their credit score -- the online intermediary supplies their application to participating banks, which can decide to offer a bid to the consumer. The web intermediary standardizes all financial contracts, reduces search costs, and allows consumers to see competing bids in an accessible manner.

2. Doctor Finding Service

Finding a healthcare provider can be difficult: comprehensive information about a doctor -- that is, including malpractice history, patient feedback, outcomes -- is rarely available in one location, and websites often present data using arcane terminology and complicated designs. This research project aims to develop and test a smart disclosure service that captures information local area health care providers and provides consumers an easy to understand interface for finding and comparing health care resources.