Main navigation

One of the most pressing questions facing social scientists is how rising material inequality has manifested itself in the political process. In contrast to other rich democracies, the United States lacks a system of public financing for its federal elections. Thus, the system of campaign finance is one of the most significant ways that material inequalities affect our democracy. Wealthy individual and organized interests continually 'vote with dollars' before most Americans make it to the ballot box. As the cost of American elections has escalated, candidates for office have become ever more dependent on these donors.

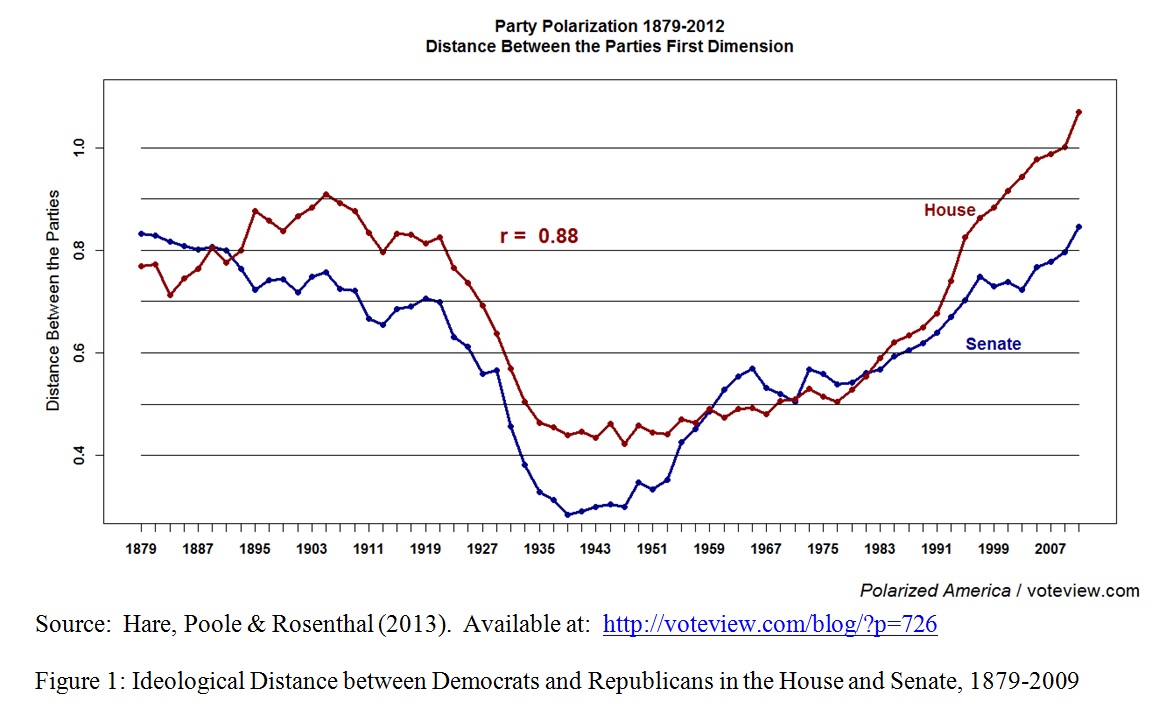

At the same time as money has grown to play a bigger role in our elections, the policy positions of the two major political parties have diverged dramatically. Political scientists Nolan McCarty, Keith Poole, and Howard Rosenthal have developed a standardized measure of how far apart the two major political parties are based on the roll call histories of members of Congress. These scores show that, since the early 1980s, the parties have moved apart rapidly. In fact, the two parties are now farther apart from each other than at any other time since Reconstruction when the nation struggled to unify in the wake of the Civil War. The distance between the parties has been driven, in large part, by the sharp rightward shift of the Republican Party. You can see the overall trend toward polarization in the figure below, which plots the distance measures since 1879.

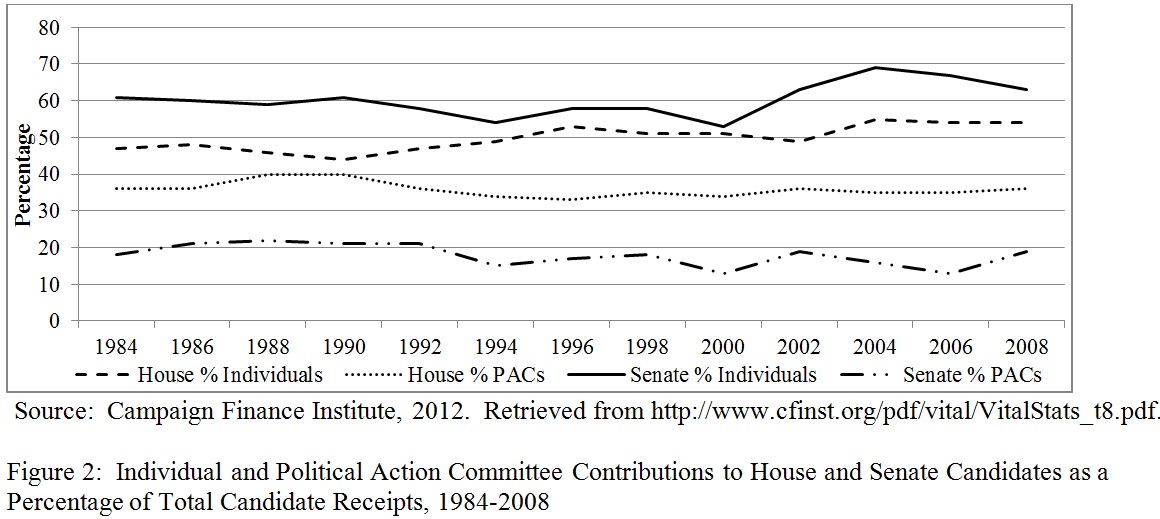

What explains this dramatic shift in American politics? Many observers of American politics have pointed to the system of campaign finance and the role of corporations—and their fundraising organizations called corporate political action committees (PACs)—as playing a crucial part in this transformation. But, in fact, the available evidence on corporate PACs suggests that they have largely continued to support both political parties through their campaign contributions, rather than lining up behind one party to advance an agenda. Corporate PACs, in sum, have remained what social scientists have broadly referred to as “pragmatic” contributors—they continue to donate to secure access to important members of Congress, rather than to pursue ideological goals.

In contrast, individual contributors have recently become a much more important player in the campaign finance system. The figure below shows the percentage of contributions that House and Senate candidates received from individual contributors since 1984. While individual contributors have always constituted a plurality of the money flowing to Congressional candidates, individual contributors now represent a larger share of candidate funding than at any other time in recent history. And, in fact, individual contributors are an even more crucial source of funding for challengers and open seat candidates. Despite the importance of these donors, social scientists have previously run up against severe data constraints in studying these contributors.

To address this gap in our understanding, I constructed an original dataset—called the Longitudinal Elite Contributor Database, or LECD—from Federal Election Commission records of donations. Unlike the FEC records, the LECD tracks individual contributors rather than merely cataloging contributions. The donors contained in the LECD are, by definition, ‘elites’—they have all given at least $200 in a federal election. In the 2000 election, for instance, the LECD shows that only 0.35% of the adult population contributed an amount over the $200 threshold for disclosure. The LECD allows me to trace how these elites have shifted their donations over time, and how aggregate strategies among all donors may have changed as well.

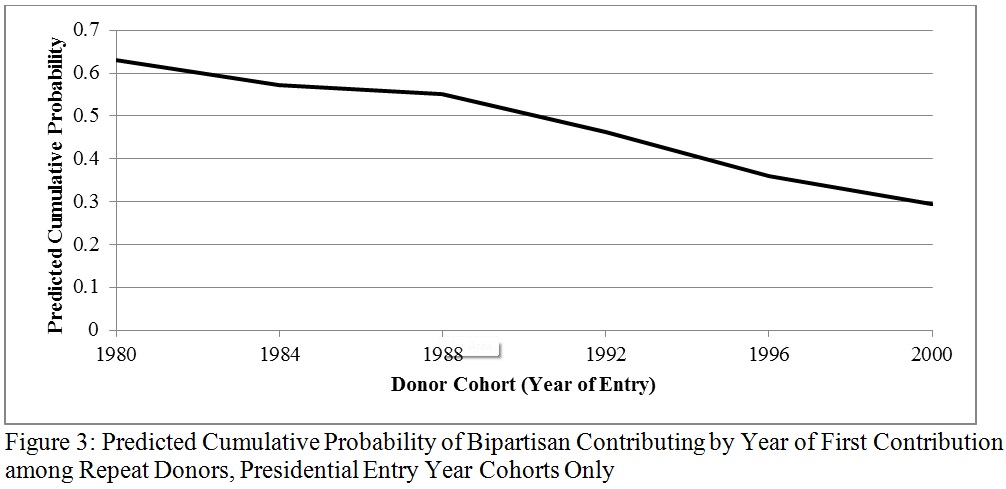

In contrast to the stability observed among corporate PACs, I uncovered convincing evidence of polarization among wealthy, elite contributors. I found very large and substantial changes in the partisanship of these wealthy elites, and in ways that were unexpected. My analyses show that a majority of large, repeat contributors who began donating in the 1980s gave to both political parties. Each successive generation or ‘cohort’ of repeat donors, however, has steadily decreased in bipartisan giving. While the large majority of donors who began contributing in the early 1980s pursued a bipartisan contribution strategy, a minority of elite donors does so today. The figure below shows this transformation. My models—which control for other factors that might drive this decline—suggest a steep drop off in the probability of more recent donors reaching across the aisle with their campaign cash.

My analyses also show that these bipartisan donors contribute, on average, to more ideologically moderate members of Congress. Thus, the decline of bipartisan contributing may have eroded an important financial base of support for middle-of-the-road incumbents and candidates for office at a time when the need for accumulating campaign cash has grown with every election cycle. In the future, my work will explore other dimensions of political polarization among these elites, and how these changes have affected the fundraising strategies of our nation’s elected representatives.

JEN HEERWIG is a doctoral candidate in sociology at New York University. In 2012, she and Jeff Manza received an award from the Russell Sage Foundation to examine the role of wealthy individual donors in campaign finance by constructing a dataset that will allow researchers to identify and examine large, repeat donors to political campaigns.